By Dr. Rex Butler

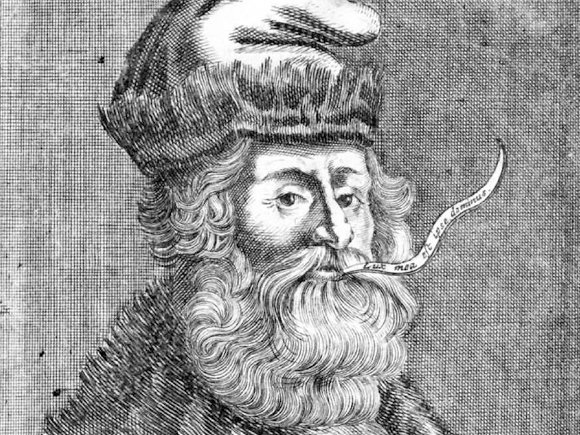

Toward the end of the Crusades, after two hundred years of conflict between Christendom and Islam, a Christian stepped forward with a new plan for approaching Muslims—not with the sword, but with the Gospel. Raymond Lull, considered the first western missionary to the Muslims, wrote, “It is my belief, O Christ, that the conquest of the Holy Land should be attempted in no other way than as Thou and Thy apostles undertook to accomplish it – by love, by prayer, by tears, and the offering up of our own lives” (Contemplation of God). Ultimately, Lull did offer up his life as a martyr in North Africa.

Lull (also spelled “Llull” or “Lully”) was born to a wealthy family in Majorca, Spain, in 1232, just a few years after it was liberated from Muslim rule. Due to his excellent education, Lull obtained a position in the royal household and married a relative of the king, Blanca Picany, with whom he had two children. Despite his marriage and position, however, he traveled about as a licentious troubadour, composing and singing love songs.

In his young thirties, Lull was converted to faith in Christ by an unusual experience. As noted in his autobiography, Lull amorously pursued a married woman, who did not return his affections. After making a fool of himself by following her on horseback into a church, the young lady came to him privately and, with dignity, bared her breast to him. Shocked that it was diseased by cancer, Lull saw in her disfigurement the corruption of his own lusts.

Not yet converted, however, Lull continued to chase other romantic interests. One night, as he was composing a bawdy song, he was confronted by a vision of the Lord Jesus Christ on the Cross. This epiphany reappeared four other times. After one long night of confession and repentance, Lull experienced divine forgiveness in the morning.

Lull abandoned his purposeless lifestyle and joined the Third Order of St. Francis. Although a Franciscan tertiary was not required to be celibate, nonetheless Lull left his family and position to pursue a life of solitude and study. Well versed in Christian philosophy as well as Jewish and Muslim mysticism, Lull’s passion turned toward the evangelization of Jews and Muslims.

In his zeal to convert Jews, he engaged in public debates with rabbis to promote their appreciation for Christian intellectualism. His great passion, however, was to evangelize Muslims. To do so, he developed a three-point plan. First, he needed to learn Arabic and other languages used by Muslims. Second, he studied Islamic literature in order to develop a Christian apologetic in response to Muslim arguments. Third, he desired to give his life as a martyr among the Muslims. From his earliest years as a Christian, he prayed, “O Lord, Thy servant and subject has very great fear of dying a natural death … for he would prefer his death to be the noblest, that is, namely death for Thy love” (Contemplation of God).

Lull’s preparation for this mission lasted nine years. During this time, Lull became skilled in Arabic with the help of his Muslim slave.

One of Lull’s ingenious methods to evangelize Muslims through logic and reason was a debating tool he called Ars magna, a “Great Art” that arranged religious and philosophical truths on rotating concentric circles. The reader then could pose a question or argument about Christianity and use the index to find an appropriate answer. For such achievements, he was awarded the title Doctor Illuminatus, and is still recognized by some computer scientists as a founding father of the information sciences.

Lull traveled extensively through Europe to promote his plan to convert the Muslims, not through Crusades but through the work of missionaries. Many times his efforts were rebuffed, but some success was achieved in Spain, France, and Italy. His most enduring results came when the Council of Vienne in 1311 decreed that the universities of Paris, Salamanca, and Oxford as well as all papal schools should teach Jewish and Islamic languages and literature.

In 1292, at fifty-six years of age, Lull set out on his first missionary journey to the Muslims. For his destination, he chose Tunis, the western center of the Muslim world and the site of the Seventh Crusade in 1254—King Louis IX of France failed with his army in his crusade, but Lull ventured forth on his spiritual crusade single-handedly.

When he arrived in Tunis, Lull challenged Muslim scholars to a series of public debates and conducted them ably in Arabic. He attacked Islam at its weakest point: the lack of love in the conception of Allah. Whereas the Muslims acknowledged Allah’s will and wisdom, they said nothing about his goodness. On the other hand, the God of the Christians exhibited all the worthy attributes of goodness, power, wisdom, and glory. Lull did not shrink from preaching the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation, which show God’s greatness and goodness, the union of Creator with creature, and God’s suffering love for humanity.

As a result of these debates, several Tunisians converted to Christianity. But Lull was imprisoned and then banished. Even after he was placed on board a ship, however, he escaped in order to return and strengthen the faith of his few converts before he finally sailed back to Europe.

Fifteen years after this mission, Lull sailed again, this time for Bugia, a port city of Algeria. He immediately proceeded to the public square and proclaimed the superiority of Christianity over Islam. Instantly, a mob gathered and attacked him. The authorities rescued him but then threw him into a dungeon, where he remained imprisoned for six months. While there he was bribed and tortured to entice him to recant his faith, but he steadfastly refused to deny Christ and continued to preach the Gospel even in prison. The Muslim authorities feared to bring him to court lest his arguments prove unanswerable, yet they hesitated to execute him because of his intellect and his favor with European kings. So they once again put him aboard a ship, this time well guarded, and expelled him. Although shipwrecked on this journey, Lull survived and arrived in Pisa, Italy, a hero of the church.

In 1315, when he was eighty years old, Lull made his third and final missionary trip, again to Bugia. This time, he labored secretly for a year to encourage and train his small circle of converts. At last, when he could restrain himself no longer, he stood up in the market place and preached publicly God’s love in Jesus Christ and God’s wrath against the errors of Islam. His audience had heard this preacher once too often. They seized him and dragged him outside the walls of the city, where they stoned him.

At this point, Lull’s biographers disagree. Some say that he died on the shore of North Africa among the Muslims he had given his life to evangelize. Others report that his friends conveyed his still living body to a ship sailing to Majorca and that he gave up his spirit in sight of his homeland. Whichever account is correct, the truth is that Raymond Lull, missionary to the Muslims, died the martyr’s death for which he had prayed often. But perhaps Lull is remembered best not for the way that he died but for the way that he lived, as expressed in his own motto: “He who loves not, lives not; he who lives by The Life cannot die.”

Dr. Rex Butler is a professor of church history and patristics and currently occupies the John T. Westbrook Chair of Church History.