I recently did a Q & A with Dr. Kevin Brown (who was previously on episode 18 of our podcast here), and we talked about the death penalty and if it fits into evangelical Christianity.

Absolutely. In a 2016 study by the University of North Carolina, researchers looked at the 155 death penalty cases in Louisiana between 1976 and 2015 that were resolved (meaning, they were previously on death row and then their status was ‘downgraded’). The study found that of the 155 cases, 127 were reversals of the sentences. In other words, 82% of the people sent to death row—who spent years waiting to be executed—were not supposed to be there in the first place. And what’s even more disturbing is that Louisiana is only about ten percent higher than the national average, making this is a national problem.

It’s not just marginally higher. In some cases—like when the victim is a white woman as opposed to a black man—it’s as much as 30 times higher. In her book The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander argues that carceral policies are unequally enacted upon the black community. She writes, “the economic collapse of inner-city black neighborhoods…coincided with the conservative backlash against the Civil Rights movement” (p. 218), adding, “it is fair to say that we have witnessed an evolution in the United States from a racial caste system based entirely upon exploitation (slavery), to one based largely upon subordination (Jim Crow), to one defined by marginalization (mass incarceration)” (p. 219). So yes, unfortunately, this is true.

They are tried before their peers, but that’s not as straightforward as it seems. According to Amnesty International and the National Association on Mental Illness, one out of every ten executed prisoners in the United States since 1977 has a mental illness. Often, those with mental illness cannot adequately comprehend or defend their situation and are inequitably impacted. They can appear unengaged, cold, or unfeeling in the jury’s eyes.

Additionally, when one considers the budgetary policies in New Orleans, where the District Attorney’s office which prosecutes crime, we see that they received almost $6.7 million, while the Public Defender’s office, who defends the indigent, received only $1.8 million. As Michelle Alexander (referenced above) has stated, in many inner-city areas, this directly affects people of color.

I believe it’s broken. According to classical criminological theory, the point of the death penalty is deterrence. Frank Fried, former head of Philadelphia’s Organized Crime Homicide Task Force, said, “the death penalty does little to prevent crime. It’s the fear of apprehension and the likely prospect of swift and certain punishment that provides the largest deterrent to crime.” Robert Morgenthau, Manhattan District Attorney, stated, “take it from someone who has spent a career in Federal and state law enforcement, enacting the death penalty…would be a grave mistake. Prosecutors must reveal the dirty little secret they too often share only among themselves: the death penalty actually hinders the fight against crime.”

Another, Willie Willams, a former Los Angeles Police Chief, added, “I am not convinced that capital punishment, in and of itself, is a deterrent to crime because most people do not think about the death penalty before they commit a violent or capital crime.” If the death penalty does not deter violent crime, then it does not suit the purposes for which it was intended.

Well, we have two options. The first is the retributive, eye-for-an-eye approach. The problem here is two-fold. First, how do you create an adequate punishment that fits the crime? Our justice system regularly struggles with this. And second, how do you ensure the right people are punished? As I’ve mentioned, our track record here is embarrassingly bad.

The second option is the restorative approach. Restorative justice works to bring healing and wholeness, which are biblical aims. It is redemptive, based upon the ideal that even criminals’ lives have value and potential to be redeemed. As opposed to the death penalty, which is irrevocable and therefore cannot lead to redemption, restorative justice provides time for God to work in the life of both the perpetrator and the victim.

I favor the second option because this is what Jesus taught. When brought the woman caught in adultery (John 8), a capital offense established by the Old Testament law, Jesus exonerated her, forgave her, and freed her from the death sentence imposed by her captors. Fully aware of the Law, Jesus showed grace and forgiveness, redeeming her to live a new and improved life.

Furthermore, this is the pro-life movement. It’s my contention that a pro-life viewpoint must be consistent; our concern is for life, not just to the point of birth, but through the entire lifespan. To honestly endorse a consistent pro-life ethic is inconsistent with a pro-death penalty stance.

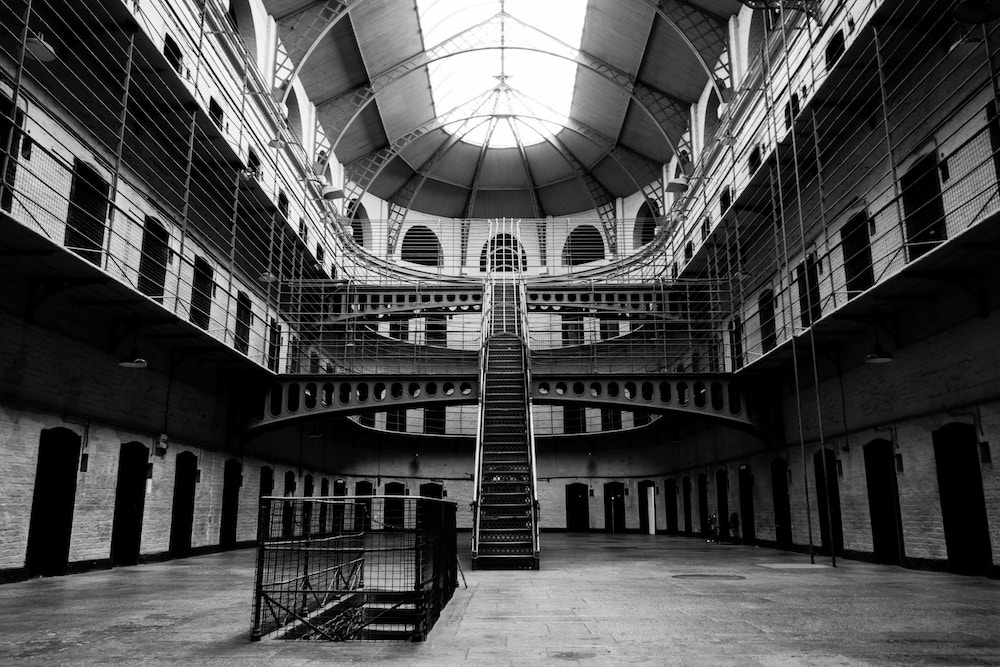

Because I’ve seen it first-hand. In my role, I oversee extension centers that provide seminary education inside six maximum-security prisons in four states. The men and women who enroll in the programs have committed crimes that would make most turn pale. A significant portion of them have received life sentences; many will never be released. Hundreds of them are involved in Christian ministry in a world that few of us will ever realize. These men and women teach others the good news of redemption in Jesus Christ, leading other inmates to a personal relationship with Jesus, discipling them in the Word, planting churches, and becoming part of incredible acts of transformation. Like Paul, they have become powerful change agents in a mission field closed to most Christian ministers.

Kevin Brown, PhD, is an associate professor at NOBTS and is the director of prison extensio center education. Joe Fontenot is the marketing strategist at NOBTS.